As you may have heard, the state and city will be spending substantial millions of dollars over the next few years to demolish vacant houses in the sections of the city that suffer from urban blight.

As you may have heard, the state and city will be spending substantial millions of dollars over the next few years to demolish vacant houses in the sections of the city that suffer from urban blight.

No doubt about it, vacant housing is a serious problem. It’s not just a visual thing. There are community health issues and it can impede economic development. Understandably, the look of blighted neighborhoods – and related concerns about crime and commerce – discourages employers from locating in disadvantaged communities in desperate need of jobs for their un- and underemployed families.

Unfortunately, state and city recourses are not unlimited. Far from it. Every dollar spent on housing is a dollar not spent on education, on the maintenance and repair of infrastructure and other important services that cry out for funding. And, needless to say, city revenues are nowhere in the vicinity of what they would need to be to cut property taxes – although few candidates for Mayor or City Council will tell you that. There is no way to lower property tax rates until the Baltimore economy grows to the point that city government can afford to provide quality education and other essential services at reasonable levels.

We need, in other words, to set priorities. The Mayor and City Council need to have the common sense wisdom and, honestly, the political balls to decline support for programs that, although very important, are just not the highest priority for the city.

We here at Baltimore Rising believe that, in a world where funding is very limited, the smart and the kind thing to do with the city’s and the state’s money is to spend it – in a very specific way – on jobs creation on as massive a scale as we can reasonably afford. Here are some of the reasons why we recommend choosing creating jobs over demolishing vacant housing…

- Demolishing vacant buildings may or may not result, eventually, in jobs creation. The process by which vacant house clearing might create jobs is highly indirect and tenuous at best. On the other hand, creating jobs first, by enticing employers to move to our disadvantaged neighbors, will, in fact, result in improvements to property for employer operations and as newly employed people spend some of their income on housing. We believe, in other words, that neighborhood improvements are demand driven. Give people jobs and income, they will demand housing and the private sector will respond accordingly.

- Only the employers themselves and their employees can know for sure where they prefer to locate. Government planners can only guess. In effect, clearing property to make way for unspecified future commerce is putting the proverbial cart before the horse.

- At the end of the day, the Mayor and City Council have to look their constituents in the face and tell them, “Good news. We’re going too spend $74 million over the next 4 years to demolish 4000 vacant houses in the city!” To which thousands of constituents will respond, “Great, but will that mean I’ll have a job? A good job that pays enough for me to feed my family?”

- And then there’s the advantage of leveraging. By leveraging, we’re referring to the ability to use government funding to secure or guaranty money employers need to expand in the heart of the city’s disadvantaged neighborhoods. Leveraging private sector money has the effect of multiplying the impact of government spending.

Suppose, for example, that a given employer with a labor-intensive need for unskilled and low-skilled workers could be incentivized to move into these neighborhoods if we can make this company an offer it can’t refuse. What might that offer look like?

For one thing, the city can give the employer vacant property that it owns. Give it to the employer for free. That doesn’t cost the city anything. Let the employer tear down or refurbish any vacant structure at its expense.

And the city can give the employer $0 property taxes for, let’s say, 5 to 10 years. Again, that would be at no cost to the city because these vacant, city-owned properties aren’t currently paying any taxes.

And the city could help the employer borrow the money it needs for setup and operations – including for providing paid on-the-job training. That sure beats having the city or employee pay for vocational training for an unspecified job that may or may not be there when he or she graduates. What you want is for employers to hire people and pay them while they are trained for the jobs they’re going to do.

How do we do this? How do we provide capital employers need? The simple answer is, by working with local banks who lend their money to these employers. Banks will, for example, let us buy down the interest rate the employer pays to make that money more affordable. Alternatively, the city can give the banks cash for perhaps 20% of the loan amount – cash the city gets back when the employer makes its payments. Cash that the bank collects for the city.

There are, of course, various different ways to do this, to leverage the city’s and the state’s money to lure employers to the city. What they all have in common is that – unlike spending money to demolish housing which is unleveraged – what we’re talking about will turn $74 million into perhaps $296 million assuming 4:1 leveraging. How ’bout them apples? That’s just plain good business, isn’t it?

Bottom line, we believe that it’s better to give employers incentives and help get people jobs and then let those newly employed families spend their money on housing – than spend money demolishing vacant houses with no assurance as to what will happen to that property after it’s been cleared.

And we believe that creating jobs to eliminate unemployment and poverty in the city – and a lot of related crime with it – is a far, far more urgent priority that deserves the attention of every dollar the city and state and get their hands on.

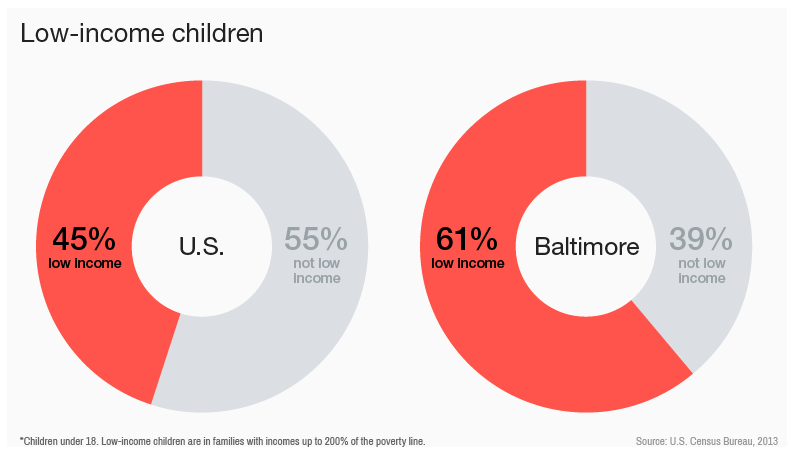

The blight in Baltimore on which our city and state should be laser-focused to cure on an emergency basis isn’t housing. It’s the inability of tens of thousands of families to provide for their children because they are either unemployed or employed, but not making a living wage. Let’s do something about putting people to work first, please. Investing in the demolishing of vacant houses is important, but needs to wait.